„You need at least 800 years for a good revolution“

► You Need At Least 800 Years For A Good Revolution

Jonas A. Zalkind, a Revolutionary from 1917

Demonstration by workers from the Putilov Factory on February 23, 1917 in Petrograd.

Source: State Museum of Political History of Russia

They were “bourgeois types” by birth. It’s a luxury to be a socialist. They showed great respect toward the delegates from Petrograd’s factories, workers who had labored at workbenches until the outbreak of the revolution.

From a class perspective, even the workers weren’t industrialized. The laborers from Petrograd’s factories displayed the qualities of the peasant class: solidarity, composure, a connection with the seasons, caution, artisanal pride. As proud as their machines as of a hedgerow, a tilled field, a wood planted by their ancestors. They all had a special kind of ownership: the ownerships of their SELF-CONFIDENCE.

Jonas A. Zalkind acted as a commissar. At times as Trotsky’s deputy. Member of the “Amalgamating Group”: lacking vanity, ACTING WITH THE EGO-BARRIER UP.

► The Revolution’s Time Requirements

What Is an “Amalgamating Group”? / Rosa Luxemburg and the Revolution of 1905

The “amalgamating group” is the element of all revolutions. People join together. Without being aware of it yet, they form, in contrast to their previous life, a new kind of condition, in which, without any volition on their part, their qualities combine. Beneath the level of their willpower, under the impression of the excitement which has gripped the city, on the strength of intuition and energy. More people come in from the country. They join the ranks. The “new revolutionary man” (an initially unstable element) does not consist of persons , of the men as they were, but emerges between them, out of the gaps which divided people from one another in everyday life.

In Kiev a pickpocket was caught up in an amalgamating group moving toward the main railway station, which it wanted to occupy. Tsarist guards tried to stop the crowd. The pickpocket was tempted by the authorities, but he forgot his trade. He became one of the scouts who reconnoitered a route for the column of demonstrators, which led by way of side streets to the square in front of the station. For several hours the lad did not steal anything. In the evening he went hungry. That day he possessed nothing but his enthusiasm.

A lawyer, whose time had always been valuable to him (lawyers are part of the service sector), had strayed into the same group. He marched through the city with the rebellious mob, and by going along with them, without wanting to (and while subjectively disapproving of such illegal and riotous assemblies), the momentum of the attack on the police cordons. He was on the streets until late in the evening.

Rosa Luxemburg (1915)

Source: German Federal Archives

Rosa Luxemburg, who had travelled to Russia from Berlin at the news, tried, having arrived too late, to reconstruct the experience of the first days of the revolution. She collected reports. They were in agreement that, at the moment of the upheaval, communications, ideas, stimuli to action spread more quickly between people than could have occurred by means of telegraphy or transport. It seemed to her, as she wrote with a degree of pathos in her articles for the Leipziger Volkszeitung, as if a SINGLE LIVING BEING, A REVOLUTIONARY TOTAL WORKER was in action. After a few days it was only memory. The “giant,” about whom Rosa Luxemburg had written, appeared to have disintegrated after a short time.

Unlike a human child, wrote Rosa Luxemburg, which is born as a tiny bundle and grows up to be an adult, the revolution is born as a giant body, as a NEW SOCIETY, and it needs time to change back into the individual human beings of which it is made up. To her the crucial question, which occupied her until the end of her life, was this: how could the GIANT BABY REVOLUTION be kept alive, fed and bedded for the first few weeks and then, above all, for the first few centuries. She believed that she had seen this SPECIAL LIVING BEING in the days after her arrival. There was no known means by which such an AMALGAMATION could have been saved over time under the conditions of everyday production or private family life. No revolution could make headway in a false life. WITHOUT REVOLUTION NO TRUE LIFE.

► I Was, I Am, I Will Be

Estimated Time Requirements for the “Alteration of the Soul-Forces”

Jonas A. Zalkind and Comrade Alexander Bogdanov, who had played chess with Lenin on Capri back in 1904, now responsible for the PROLETKULT project, were drinking tea together. It was the fourth hour of the night. These two restless spirits flaming brightly.

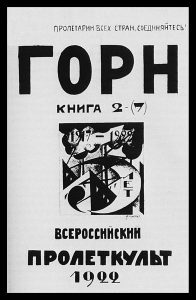

Cover of the Proletkult magazine “Gorn,” 1922

What do you see in your mind’s eye? Dialogue is a flying machine. Politically, it is imperative that Russia’s working class and peasant class must not merely form a coalition (which could only exist temporarily), but fuse into a third thing. Let us call that the “new person.” Though the sheer sight of the tractors to be delivered to the countryside, this person transforms the grain into zeppelins and airplanes that put vast Russia at close range; through the usefulness of the industrial product such people create UTILITY VALUE IN THE MIND, just as the proletarians in the factories (or in the armored trains, the ships, the ranks of the Red Army) had always carried the scent of fresh sausages, of freshly-baked bread in their hearts and in their nostrils, both workers and peasants at once. Fusion means casting off errors.

For the production of the flood of airplanes required to connect up Russia’s elements, Bogdanov and Zalkind (there’s rum in the tea) estimate a mere seven years. But for this sort of “progress” and “flood of products” to be accepted internally, for the drivers of reindeer sleds in the far north to experience the “need” for airplanes as their own need, just as the pilot incorporates the advantages of reindeer in his own “need”, for all this Russia will need thirty years. And then, Zalkind adds, there are the schools. They’ll be itinerate schools, because the widely scattered comrades need to be reached, indeed the people who do not even see themselves as comrades yet. It will take another sixty years, Bogdanov works out on a scrap of paper, to anchor the achievements of the socialist economy so firmly within the people that the socialist doctrine of virtue becomes a pleasure, something that motivates people spontaneously. For organization is spontaneity, autonomy.

“Whatever the philosophers may say – /

Even in virtue we strive for pleasure.”

► The Concierge Of Paris

Porträt des Marquis de Condorcet (1743-1794)

Successor to d‘Alembert as secretary of the Academy of Sciences and Voltaire’s pen pal, the earnest Condorcet, whom Jules Michelet called the “last great philosopher of the eighteenth Century,“ threw himself into the “waves of the revolution.” Two year earlier, he had married his young wife, Sophie. Sophie de Condorcet, née Grouchy, was twenty-two years of age and twenty-one years his junior. She was known for her essay Lettres sur la Sympathie (1798). When Condorcet asked for her hand in marriage, she explained, “her heart was no longer free.” She was unhappily in love with another man who did not love her in return. And for two years, both Condorcets lived chastely, each with great respect for the other’s feelings. But then on that day in July when the Bastille fell, in the enormous emotional commotion of the moment, Mme Condorcet conceived her only child. In April 1790, nine months later, the child was born.

At this point, Condorcet began a kind of third life. He first was a mathematician (under d’Alembert), then a public critic (alongside Voltaire), and now, “he set sail on the ocean of political life.” This earnest man was full of panache. His sharp-witted “Letter from a Young Mechanic” was evidence that he could not do without an old joke. He got involved in the question whether there should be a republic, a constitutional monarchy (and if so, how should it be established?), or merely a modification of the royal ministries. In Condorcet’s letter, the young mechanic obliges himself for a minimal fee to create a CONSTITUTIONAL KING that with occasional and meticulous repairs would be immortal. Such embellishments made Condorcet suspicious in the eyes of the Jacobins and unpopular among the royalists.

He made no mistake about the danger of his situation. It was not foreseeable which of the forces would win the upper hand in a civil war that at that point still went on. Because of possible repercussions, he later feared for his wife and their young child, the creature from the “sacred July days from the year 1.” He secretly sought out a port from which his family could flee and ended up choosing Saint Valéry.

► End Of Revolution

View of the Tiananmen Square Massacre from the Revolutionary Museum

Manfred Seifert was a spy for the GDR from Department IX of the HVA. He accompanied comrade Krenz to China in the summer of 1989. The celebrations there marked the 40th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Owing to his thorough training at the workers’ and farmers’ faculty at Halle University, the 200-year return of the Great French Revolution echoed loudly in his heart. In that moment, however, the comrade was in the rooms of the REVOLUTIONARY MUSEUM at Tiananmen Square.

The party had sent him to buy original manuscripts by Marx at an auction in England, and he had brought them along as a gift from the State Council to the Central Committee of the PRC. They were stored in the museum’s safes. Now he looked through the large windows of the monumental building, together with other comrades, including French ones, and watched the events outside: the fleeing people, the impact of shots, the attempt to set up improvised barricades which were, however, no obstacle to the personnel carriers and tanks of the military forces.

The display cases behind the observers, which contained the incunabula from earlier revolutions, reflected the conflagration: in the eyes of Seifert, the trained observer, this created a disturbing picture. Certainly, he had nothing against hooligans being expelled from the square. But he had his doubts, which were clearly shared by the other comrades present, that these were hooligans. Admittedly, using the cardboard Statue of Liberty was a provocation, indeed an act of tomfoolery. But the movement itself, based on the impressions from the previous days, the wall newspapers, the conversations Seifert had had, did seem to possess revolutionary attributes. Only yesterday he had believed that the revolution was rearing its head once again. Party discipline did not prevent him from preserving his impressions inwardly. Where do the people end, where does hooliganism begin? Who decides the form taken by outrage?

► End Of Industrial Age

Grammar of the Revolution

All epochal events first occur as tragedies and are repeated as farce, but then, says Sigrid, they return as (a) normal event. Only my husband doesn’t return, he shot himself. Even as she was speaking, she thought her conclusion “unbalanced”. No one talks “conclusively” nor “condescendingly” about the revolution and a determined dead man. The exchange took place in a beer garden in the eastern part of Berlin. Festoons(?) and electric lights illuminate the (beer garden) decor, the back-house facade behind the open air stage, the trees. Beer gardens, pleasure gardens(?) of this kind are traditional meeting places of the workers’ movement, cultivated by the Party in the 1920’s as working class culture, then returning as farce and incorporated as stage sets in political revues/variety shows in the Friedrichstadt Palast, also a farce as State Beer Garden (because no one drinks beer in a protected historical monument). Now, however, after the defeat of the working class movement in East and West, this establishment, under the patronage of a popular theatre , has again been incorporated in the habits of a target group and appears to those, who don’t decode the historical context, as a particularly pleasant place in summer, where one can meet interesting young people.

Sigrid had already arrived around 5 o’clock and had been talking excitedly and restlessly for a long time with her gang/mates. Then she sat down a little way from them and wrote in a notebook she had brought with her. Her friends left her in peace; the group were talking no more than 4 yards away (from her), fended/warded off insistent/obtrusive questioners or young men, who wanted to approach Sigrid. In every other open air establishment on a Saturday night there’s group pressure/compulsion to the extent, that someone reading or writing has to be fetched back into the noisy company of conversations and friends. Sigrid was privileged. In 1987, as a young girl, she had become the husband of/married a high-ranking cadre in Thuringia, who at the end was even transferred to headquarters as a reformer, and who, in January 1990, when the defeat of the the workers’ state was certain, shot himself. Because he had left her in the lurch, she hated him. She was too young to have (already) experienced/felt the too short marriage as (a) reality. What she felt was the aggression/violence/fury of the act. The/Her numbness after he was buried. For her earlier/former friends the act was a private matter.

Sigrid writes: “I WAS, I AM, I SHALL BE, these are the last words in Rosa Luxemburg’s article in Die Rote Fahne [The Red Flag] of 18th January 1919, published just before her murder. These are words spoken by the Revolution. It has always been the engine of history, it/and will return after its violent suppression, and, without anyone noticing, it is always there as (an) inner voice, grist of time, humming machinery/mechanism.”

At the moment unfortunately, writes Sigrid, it is not here in the Prater.

Reents, who works for Gysi , forces his way through the wall of friends to the writing Sigrid. He reads the text, he reads the heading: “Grammar of (the) Revolution”.

Characteristics of a Female Citizen on Travels

Where Is the Face of a Bourgeois Soul Located?

On her travels in the Soviet Union, the daughter of the millionaire, United States Ambassador to Germany and confidant of Roosevelt, Dodd, suffered greatly due to the conditions in the toilet of the small steamer on which the tourists were going down the Volga. The installations were made of cast iron and crudely painted. Their surfaces were so rough that any foreign body, any dirt stuck to them for years. This millionaire’s daughter did not want to sit down on such a thing with her Western bottom. Instead she squatted above it, her muscles tense with the effort, seeking to avoid contact with the cast iron and the paint.

Shortly before Astrakhan she made the acquaintance of a young man, a Soviet secret agent, who later described her as follows: ‘I encountered a bourgeois lady. These bourgeois ladies clean their anuses, on which they sit just as we do on ours, more scrupulously than their faces. The latter is exposed to the air and the weather and cleans itself, as it were. Occasionally the bourgeois ladies support the skin of their faces with a hint of cream. At the same time, such a bourgeois lady takes little rolls of soft paper (unsuitable for writing on) with her. There are no notes written on these little rolls (I checked thoroughly); their purpose is to clean the anus after the activity itself and then be carelessly thrown away. The supply of such little rolls is “sacred” to the person under observation, the bourgeois lady. She became very upset when her power to dispose over these little rolls (through a manipulation of ours, a test) seemed lost for a few hours. I subsequently “found” the “papers”, to her relief, without her ever learning why we had removed them.

‘The bottom is especially sensitive among bourgeois ladies. Evidently this young woman was never struck on her bottom with a rod. She responds to stroking of this anti-face, her most important skin organ, with affection. Also sensitive on the shoulders, the neck, behind the ears. The lips, on the other hand, which we Soviets use to accompany contact, have a more defensive function.

‘She demanded absolute confidentiality regarding everything we exchanged in the short space of a few days. This applied most of all to the staff of the US Embassy, whom we soon met in Astrakhan. I was not able to ascertain any anti-Soviet activities or secret knowledge (aside from the personal customs and erotic habits of a bourgeois lady). Signed A. M. Shvirin, Major.’